│Wisconsin State Government│Preemption│Wisconsin State Budget│Educational Advocacy│

│Entry Points for Public Policy│Coalition Building│Community Events│

The Policy 101 Toolkit provides a basic overview of the Wisconsin policy making process. This resource is not intended to provide legal advice regarding policy development and advocacy. Individuals and organizations should always seek legal counsel for such advice and, as interpretation of laws may vary, you should regularly stay abreast of current rules and guidance around policy work, including municipal ordinances in your jurisdiction.

Framing and Defining Health Equity

This toolkit should be reviewed and studied with a health equity lens. It is important that this lens not be an afterthought but a framework that is at the forefront and leading the work.

Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be healthier. This includes a fair, just distribution of the social resources and social opportunities and requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access. (Braveman P, Arkin E, Orleans T, Proctor D, & Plough A, 2017; ASTHO, 2000)

Please refer to the Policy 101 Key Terms document to define many of the terms used throughout the Policy 101 Toolkit.

Wisconsin State Government

Bicameral Legislature

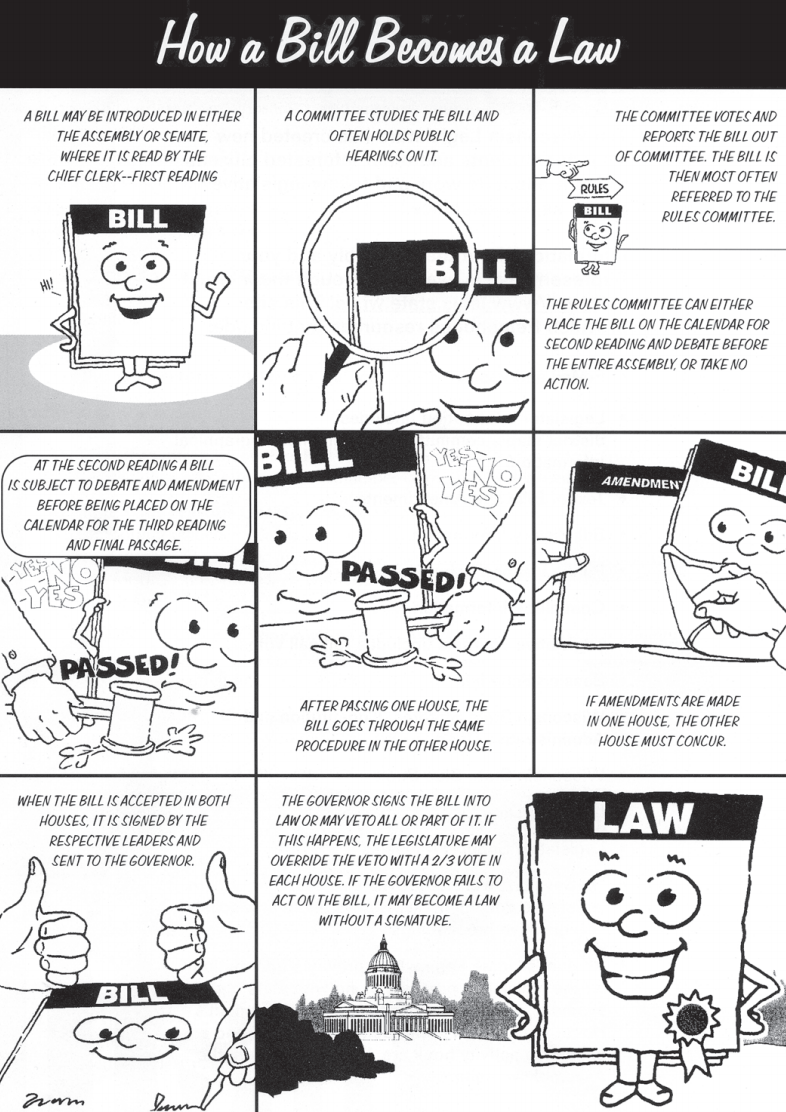

Wisconsin has a bicameral Legislature, which means there are two houses, the Senate and Assembly, that have to agree by voting to pass proposed legislation into law. Then the governor considers the bill for signage or veto.

The full Legislature is made of 132 legislators, 99 Assembly Representatives and 33 Senators. The state is comprised of 33 Senate districts, and each district elects one Senator. Each Senate district is then divided into three Assembly districts, 99 in total, which each elect an Assembly Representative. Every home address in Wisconsin has both a Senator and an Assembly Representative.

Assembly Representatives have two-year terms. Senators have staggered four-year terms. Every two years, we vote on either the odd numbered State Senate districts or the even numbered State Senate districts. For a detailed breakdown of members in the Assembly and the Senate, visit the Wisconsin State Legislature homepage.

Fig. 2. The Wisconsin State Legislature. (n.d.) How a bill becomes a law [PDF]. Retrieved from https://legis.wisconsin.gov/assembly/acc/media/1106/howabillbecomeslaw.pdf

Preemption

Preemption is a legal term that means higher levels of government have the authority to limit the power of lower levels of government on specific issues involving policy creation and implementation. Lower levels of governmental policy cannot conflict with or be stronger than the higher level of governmental policy. For example, if local or state law conflicts with a federal law, the federal law will overturn and take precedence over the lower level of government’s law. Likewise, state law can override local law if local law is not in alignment with state law.

Wisconsin is a “Home Rule” state, meaning that the most local units of government control lawmaking unless a specific issue is preempted by state or federal law.

Examples

Policies surrounding tobacco regulation are often preempted. The tobacco industry pursues preemption in state statute and through legal challenge because the strongest tobacco prevention and control policies typically pass at the local level first, before they are passed at the state level. Without local action to adopt strong, comprehensive best-practice public health policies, it is less likely that best practice tobacco prevention and control policy will pass at the state level.

In Wisconsin, state statute preempts local action in areas that include:

- tobacco taxation

- age restrictions

- youth access (product placement, flavorings, and point of sale advertising)

- smoke-free outdoor spaces in businesses.

Any locality pursuing a policy that is expressly preempted in state statute or through interpretation of the 1996 Wisconsin Court of Appeals U.S. Oil Inc. v. Fond du Lac case law risks legal challenge from the tobacco industry and its allies.

Examples of tobacco-related policy that are not preempted include:

- clean indoor air in all workplaces (adding vaping, e-cigarettes, and marijuana)

- clean indoor air in government-run facilities (including behavioral health and prisons)

- tobacco-free public lands (parks, beaches, trails, etc.)

- zoning restrictions on retailers.

Another couple of examples of Wisconsin preemption include restricting single-use plastic bags and setting a minimum wage above the state minimum.

Wisconsin State Budget

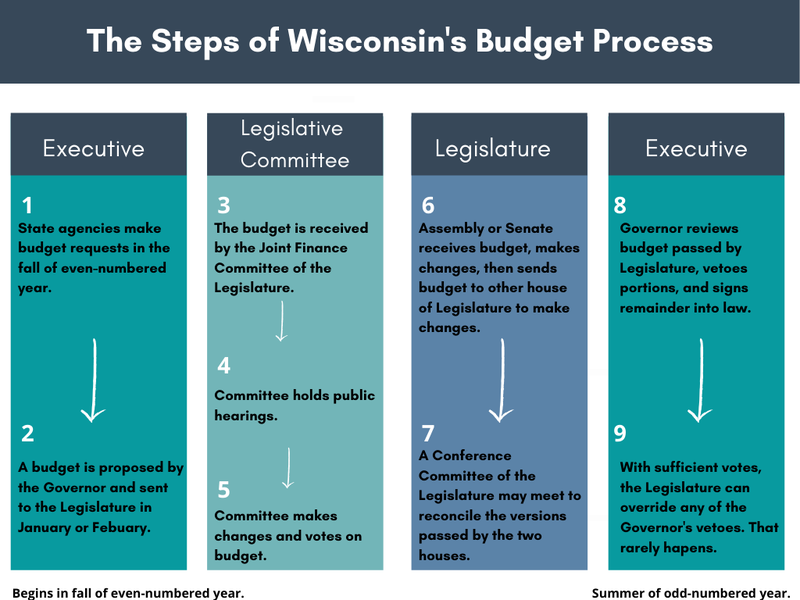

Image adapted from: http://www.wisconsinbudgetproject.org/budget-toolkit/the-wisconsin-budget-process

How Does the State Budget Impact Me?

You are impacted by state budget decisions countless times every day. When you turn on the water, send your child to school, turn on a light, or drive on a road, you are impacted by state spending. You help pay for these and other benefits every time you buy something, get paid, or by owning property.

The budget must be balanced; the state can only spend as much money as it collects through taxes, fees, and other sources. Decisionmakers must weigh priorities against each other. Ideally, the state budget reflects our public priorities.

- Wisconsin has a biennial budget. This means that the state budget includes information about how money will be spent for a two-year period.

- For example, the 2019-21 budget runs from July 2019 through June 2021.

- A fund of money raised by the state mainly through taxes.

- GPR is available for appropriation by the Legislature for any purpose.

- During gubernatorial and legislative campaigns, ask about tobacco prevention and control issues as part of candidate forums and debates. Make sure you vote and get others to vote as well.

- Keep in mind coalitions are subject to electioneering scrutiny. It’s important to keep communications the same to all candidates in a specific election, so actions cannot be misconstrued as electioneering.

- Follow the budget process through its drafting, Governor introduction, and Joint Finance Committee processes. Inform members of opportunities to engage in the process, and when the budget allocations change or advance throughout the process.

- Provide verbal or written testimony during the Joint Finance Committee (JFC) hearings, for educational information only.

- Remember that the Tobacco Prevention and Control Boundary Statement restricts lobbying in any form. Click here for a reminder of Educational Advocacy versus Lobbying.

Educational Advocacy

Meeting with legislators and stakeholders to provide educational information about issues that are important to you is one way to generate policy movement. These education-based interactions can occur during community events, personal meetings, formal presentations, media coverage, or public testimonies. Explore the Educational Advocacy Toolkit and the resources below to learn more.

- 30 Tips for Good Advocacy

- A Citizen's Guide to Participation in the Wisconsin State Legislature

- Hosting a Successful In-District Meeting

State grantees are prohibited from lobbying with state resources but there are many non-lobbying activities that you can conduct. Visit the Educational Advocacy vs Lobbying page to learn about Direct Lobbying, Grassroots Lobbying, and Educational [FT1] Advocacy.

Health Equity at the Forefront

- Assess the policy context that creates underlying systems issues that perpetuate inequities.

- Does our organization have the knowledge, skills and resources needed to identify the policy context for health inequities?

Media Advocacy

Media campaigns, combined with interventions, are an important high-impact strategy. Use the Media Advocacy Toolkit to plan and execute your media strategy.

Message Mapping

A message map is a tool for achieving message clarity and consistency when talking to the press or the public about a particular issue.

- Organize information in an easily understood and accessible format.

- Express a group’s viewpoint on important issues, questions, or concerns.

- Promote open dialogue both inside and outside an organization.

It’s often tempting to load your story with as many facts, figures, and messages as possible. However, on average, people can only digest three messages at a time. Message mapping can help ensure that you’re getting your point across in the way you intend. Here’s how you do it:

- Ask yourself “If I could only tell people three things about this story, what would they be?”

- Keep in mind, each of these messages should be short, simple, and to the point.

- Once you have your three messages, then ask yourself “Which two are most important?”

- Your top two should be your first and last key message (your least important point goes in the middle).

- Now that you’ve got your three, what are some supporting facts or points for each of them?

- Once you’ve got your message map in place---use it! You may be tempted to stray from it, but stick to the messages you outlined in the map. It’s there to help you as much as it is to make sure your audience gets your point.

- Conciseness - Limit the map to three main messages

- Brevity - Keep your messages short – It should take nine seconds to communicate all three messages combined

- Clarity - Your three messages should be comprised of no more than 27 total words

- Identify who you want media outlets to contact when future stories arise.

- Your spokesperson can vary depending on the story- think about who the expert might be for various topics and who the target audience is most likely to connect with and trust.

Use this Message Map Template to develop your clear and concise talking points.

Social Media

The use of various social media platforms is a powerful tool to reach target audiences with strategic and effective health communications and interventions.

Best practices to keep in mind:

- Use highly visual posts.

- Every editorial calendar should be reviewed by a peer or superior prior to publishing. This second pair of eyes will be helpful in spotting misspelled words and ensuring the right type of post is going on the correct channel.

- Keep it short and sweet. Shorter posts are easier to digest, easier to read and easier to pass along.

- Twitter: 71-100 characters; no more than 2 hashtags

- Facebook: 40 characters

- Instagram: Poster’s discretion, but keep the hashtags at 6 or under

- Post during active hours for your audience.

- Tailor your post to the social media channel – verbatim language should not be used on every channel.

- Create posts that encourage conversation, not one-way broadcasting.

- Sign up for Google Alerts. You can cut your brainstorming time in half if Google is doing the research for you.

- If you’re creating your editorial calendar two weeks or more in advance, leave a couple of blank slots so you can leave room for current event posts.

- Reward contributors. Empower your followers to help build your social media channel.

- Revisit your social strategy once a quarter at minimum. Social media channels evolve over time, so should your approach.

Health Equity at the Forefront

- Who is shaping the narrative?

- Who are we lifting up? Who is missing?

- What are trusted sources in your community? Where are folks with lived experience receiving information?

It is important to note when engaging in narrative work, stories of communities most impacted should not be extracted or feel transactional. Lived Experience is experience, and storytellers should be compensated, whether that be fiscal or in other ways.

Entry Points for Public Policy

Good policy work can take many shapes and forms. Policy isn’t limited to bills debated by the State Legislature. A wide variety of groups make decisions that impact health - elected officials, government employees, volunteer committee members. The groups shape policy in varied ways. This means that you can influence the policy-making process from many different entry points to improve community health.

Explore the tabs below to learn about a variety of entry point opportunities.

Opportunity: Government agencies collect, standardize, and disseminate information and data. Sharing data or standardizing data elements across agencies can ensure more effective collaboration.

Possible Actions: A local health department shares tobacco use data with a state leader, or an alliance collects retailer assessment data around tobacco, alcohol, and nutrition sales practices.

Opportunity: Planning decisions play a role in shaping how communities grow and change. While these plans often go in front of elected officials for final approval, the initial plans are usually drafted by groups such as comprehensive planning departments, parks departments, or economic development organizations.

Possible Actions: The parks department plans for a new playground in a rundown park where many teens go to smoke. A planning department includes safer crosswalks or bike paths into a plan to redo city streets.

Opportunity: Local resolutions reflect consensus among the governing body without changing law.

Possible Actions: The Wisconsin Association of School Boards passes a resolution to reflect a widespread commitment to ensuring learning environments free from e-cigarettes. A county board passes a Health in All Policies resolution that directs the county to consider health impacts in future policy decisions.

Opportunity: Permits and licenses authorize or limit particular types of activities or development. Zoning, for example, is used to divide land into areas for allowable uses.

Possible Actions: A city council creates a limit on the density of tobacco retailers allowed or determine a safe distance for tobacco or alcohol retailers to operate from schools. A village board does not allow land adjacent to senior housing to be rezoned for a large industrial development.

Opportunity: Local ordinances provide funding for or authorize new programs, regulations, or restrictions.

Possible Actions: A city council amends a local smoke-free workplaces ordinance to include e-cigarettes. A county board passes legislation to regulate runoff from large farms.

Coalition Building

What is a Coalition?

A coalition is a group involving multiple sectors of the community, coming together to address community needs and solve community problems. Coalitions demonstrate people power, shared interest, and mass support of a particular policy direction.

- Coalitions can be called many things, such as an alliance, network or collaborative.

- Coalitions cannot be made up of one person. They are organized for mutual benefit.

- Coalitions work best when they involve partners from many sectors in the community.

- Coalitions gather together collaboratively.

- Coalitions are founded on the purpose or promise to solve a community’s problems.

- Acts as a catalyst for change

- Gathers or convenes people

- Supports collaborative problem solving

- Builds and sustains leadership development

- Builds and maintains coalition structure that fosters relationships with those most impacted by the coalition’s work

- Externally run or externally driven organizations. Coalitions must have a strong base in the community.

- Human services organizations. Coalitions work best as catalysts to action, not service providers.

- An automatic link to grassroots or “real people." Outreach efforts and engaging citizens is required.

- A cure all. Outside factors still play a role, for example, coalitions are still affected by the political environment.

- Efficient. Collaboration is not about efficiency and is not required for all things.

- Stable or predictable. Unexpected happenings may occur, it is important to be flexible.

Coalition Building Tools

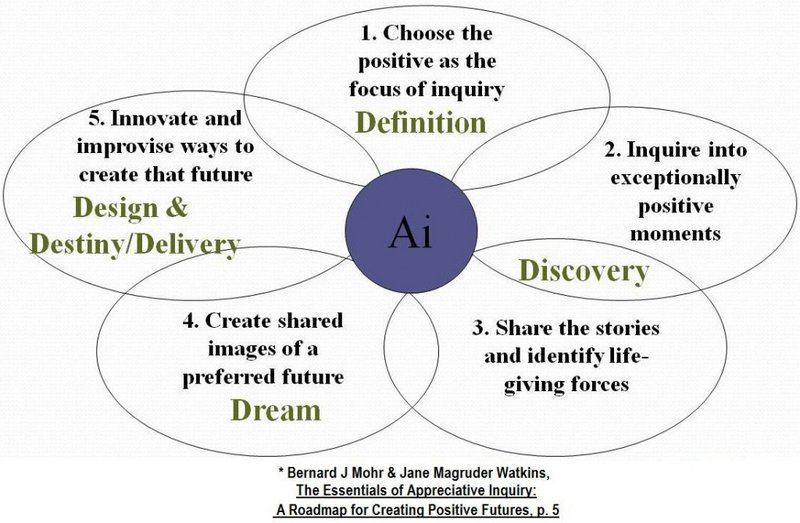

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) seeks to engage people in self-determined change, based on the premise that every person has wisdom, and every system has strengths to offer.

Evidence-based reasons to use Appreciative Inquiry:

- Solution-based approaches change the basic orientation from problem-focused to possibility-focused

- Focuses on turning the negative or problem into an opportunity

- Renewal of energy, hope, motivation, and commitment

- Increased curiosity

- Improved conflict resolution

A One-on-One Conversation is an intentional conversation with a person. This is not a casual chat. The goal of a One-on-One conversation is to build a relationship with the person by understanding who that person is, what their “story” is, and to map out possible connections.

Important Rules:

- Active Listening

- Follow the 80/20 rule. The person who called for the One-on-One should spend most of the conversation listening, they should only be speaking 20% of the time. The person who was invited to the One-on-One should be speaking 80% of the time.

- Asking Powerful Questions

- Discover self-interest through powerful “what” and “why” questions

- You have been in the neighborhood a long time, how have you seen it change?

- What are your concerns as a parent sending your kids to the public schools?

- Probe further with "why" questions

- Why are you concerned with that?

- Why is that important to you?

- Connect their self-interest to next steps

- When we hold this meeting, would you be interested in attending?

- Is it okay if I follow-up with you about ***?

- As we discussed, can you connect me to so-and-so? Do you need anything from me to make the connection?

- Discover self-interest through powerful “what” and “why” questions

A Grasstop is a person who represents a specific group of supporters or constituents.

Their participation in coalition activities is assumed to represent the voice of this defined group of voters who they represent/influence. Grasstops include non-profit leaders, business owners, health system representatives, newspaper editors, social media influencers, and elected officials.

Planning for Your Coalition's Interventions

To ensure coalitions and networks are using their time and resources most effectively, complete an environmental assessment to clarify the community's demographics and needs. An Environmental Assessment is the first step in building coalition support that will most effectively drive public health practice and social norm change. Community Readiness Assessments help a coalition select a “right-sized” intervention for their community and help them from feeling stuck.

To learn more about Environmental Assessments and Community Readiness Assessments visit the Local Initiatives Toolkit.

Health Equity at the Forefront

- Who are the communities most impacted by the inequities you want to address?

- Does this approach engage folks that are marginalized and/or experience inequities?

- Consider the following:

- Are they part of the action plan?

- What role do they play?

- Do they have decision-making power?

- Consider the following:

An important step in the assessment phase is to analyze specific interventions through a health equity lens. The Racial Equity and Social Justice Initiative at the City of Madison created tools that allow for conscious consideration of equity during the policy process. Fill out an Impact Analysis Tool to assess the health equity impact of a specific policy.

To learn more about the Impact Analysis Tool visit the Local Initiatives Toolkit.

You can connect with and influence your targets through your allies. Therefore, it is important for your coalition to identify existing connections between coalition members and decision makers.

Visit the Map Coalition Network section of the Local Initiatives Toolkit to learn how to use the Circle of Influence Exercise for strategic planning around existing institutions and leadership structures.

Once you have completed the Community Readiness Assessment, identified, and selected an intervention to address the community health problem, you are ready to created a detailed plan that clearly describes the intervention and what you hope to accomplish.

The action plan is expressed in terms of goals, objectives, and activities with expected results. It includes a target date for each activity, a description of key resources needed, and establishes accountability. A carefully designed and well-written action plan provides a solid basis for project evaluation.

Guidelines for creating an Action Plan

Always consider the following equity questions when creating your action plan:

Community Events

Community Events are a valuable strategy that can be used to educate constituents and legislators, unify current and potential partners, and promote the work that is being completed by your coalition.

Explore the Community Events to guide your event planning. Use Overview of Community Events to identify which event type best suits your need.

Health Equity at the Forefront

- What are the assets in your community?

- Have the possible strategies taken into account your community assets?

- Will the strategies advance equity?

- Will the strategies create inequities or widen gaps?

- In what ways?

- How do you know?